Tác giả nổi tiếng

Daniel McCallum

Daniel Craig McCallum (21 January 1815 – 27 December 1878) was a Scottish-born American railroad engineer, general manager of the New York and Erie Railroad and Union Brevet Major General during the American Civil War, known as one of the early pioneers of management. He set down a set of general principles of management,[1] and is credited for having developed the first modern organizational chart.[2]

Biography

McCallum was born in Johnstone in the council area of Renfrewshire in the west central Lowlands of Scotland in 1815. In 1822 his family emigrated to New York, when he was still a boy. They settled in Rochester, New York, where he spent a few years at elementary school. He didn’t want to follow his father’s footsteps to become a tailor. Instead he left school to become a carpenterand worked his way up.[3]

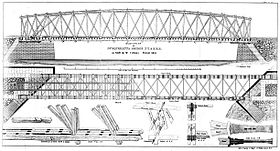

Early 1840s McCallum worked as an engineer in Rochester, where among other buildings he designed the Saint Joseph’s Church. By the 1840s he started building and maintaining railway bridges as subcontractor for the New York and Erie Railroad.[4]Late 1840s McCallum became in charge of the bridges of the New York and Erie railroad,[5] where he started experimenting with new construction methods. He developed and in 1851 patented a new type of bridge, named the “McCallum Inflexible Arched Truss Bridge”. Which could withstand heavier loads[4] and required less maintenance than previous designs. One bridge was built at Lanesboro, Pennsylvania over the Susquehanna River, which enduring construction drew national attention.[5]

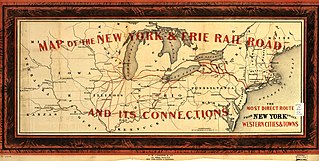

Early 1850s at the New York and Erie Railroad Company McCallum was promoted to superintendent of the Susquehanna Division,[4] one of five operating divisions of the railroad.[2] And about two years later in 1854/54 he was further promoted to General Superintendent of the New York and Erie Railroad as successor of Charles Minot under Homer Ramsdell‘s presidency. In this position he supervised the entire railroad and restructured the organization to make it more efficient and safe. He introduced new management and communication methods using the telegraph. He also described these new principles of management, and introduced the first modern organizational chart[2] as a way to manage business operations.[6] On 25 February 1857[7] McCallum resigned from the Erie Railroad and founded the McCallum Bridge Company in 1858.[8]

During the American Civil War the Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton appointed McCallum Military Director and Superintendent of the United States Military Railroad with the staff rank of colonel. He was brevetted brigadier-general of volunteers for faithful and meritorious services in 1864, and to major general in 1865. In July 1866 he was mustered out of the service, and published a report on the military railroads during the war.

MacCallum also wrote a set of poems.[9] The most famous was called ‘Lights on the Bridge’, which he wrote shortly before his death for his friend, Sam Campbell, who was a fellow railroad engineer killed in 1842. McCallum himself died in Brooklyn, New York, 27 December 1878.

Work

Architecture, 1830s-40s

McCallum was an architect in Rochester from 1840, and for a few subsequent years.[10] He was an accomplished architect and held a high position in his profession.[11] Among the prominent buildings erected by him are the House of Refuge, St. Josephs Church, St. Marys Hospital, and the Odd-Fellows’ Hall building. He did much to improve the general architecture of the city. His drawings and studies were carefully made, and his plans well-adapted to location.[11]

The St. Josephs Church was originally built 1843-1846 in the simple monumental tradition of the Greek Revival, with a gray stone facade of series of arched bays on the exterior facade. The simple church was enlarged 1849 into cruciform plan that sat a thousand. The interior was remodeled in 1895. The first steeple added in 1859 and replaced with a tower in 1909, designed by Joseph Oberlies.[12][13] Nowadays only the preserved facade of St. Joseph’s Church has remained.

McCallum’s Patent Timber Bridge, 1840s-60s

Late 1840s McCallum developed a specific truss bridge construction for the railroad bridges, called McCallum inflexible arched truss. It was constructed principally of pine timber, with less than the ordinary portion of iron rods, blots and casings.[5] An editorial notice from Appletons’ Mechanics’ Magazine, edited by Julius W. Adams commented on McCullam’s Patent Timber Bridge, built in 1851 over the Susquehanna River, near Lanesboro’, Pennsylvania, for the New York and Erie railroad.

- We have no hesitation in affirming, that of all the timber bridges patented in this country, there are none, in point of strength, economy (in which we include ultimate durability), facility of repair, and uniformity of action, to be preferred before this plan of bridge lately patented by Mr. D. C. McCallum, of Oswego, engineer or ways and structures on the New York and Erie railroad.

The bridge shown in elevation (see image) has been built lately for the New York and Erie railroad, at Lanesboro’, over the Susquehanna river, in the place of one built by ourselves, several years since, under the orders, and according to the plan of the chief engineer of that road, but which proved unequal to the duty imposed upon it; and its removal became a matter of necessity.

We objected to the plan of the original bridge, built in that locality, as we have ever done to any plan of bridge in which the attempt was made to unite the independent systems of arch and truss, and make toe stability of the bridge dependent upon their uniformity of action. In this plan of Mr. McCallum, the two principles are not independent as heretofore; but the action of the arch in the upper chord is made an integral part of the truss itself; and instead of two systems acting unequally, and to the ultimate injury of the structure, we have the best features of both united in a manner which admits of entire uniformity of action.

In the construction of bridges for railroad purposes, two prominent difficulties have long been discovered, viz., a lack of sustaining principle towards the ends of the trusses and near the abutments, and an entire absence in many cases of a proper counteracting principle to prevent vertical vibration by a moving load. See Haupt on Bridges, to which admirable work the reader is particularly referred for a full description of the proper office of a counter-brace…[5][14]

These inflexible arched truss were used in wooden railroad bridges across the US and Canada in the 19th century. After his work at the New York and Erie Railroad, in 1858 McCallum founded the McCallum Bridge Company in Cincinnati. The company specialized in railroad bridges, which they build in the Western and Southern States.[15] Some of the Howe truss men were so impressed by McCallum’s business success (if not by his arguments) that they began arching their top chords, and a notable example of this practice was the Rock Island Bridge over the Mississippi River.[16] The advent of steel bridges in the 1860s effectively made obsolete his unique design.

Large-scale management problems at New York & Erie Railroad, 1850s

McCallum had started at the New York & Erie Railroad as subcontractor to build and maintain bridges, was appointed superintendent of one region and eventually made it General superintendent in 1855, controlling over 5000 employees. In this position McCallum came in contact with the large-scale management problems, which other great railroad companies such as the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad also faced.[17] One of the main problems of these largests railroad companies was the rising of costs of moving freight in compare to smaller companies. McCallum postulated that this was caused by inefficient internal organization. In his 1856 report to the stockholders of the New York & Erie Railroad he explained:

- A superintendent of a road fifty miles in length can give its business his professional attention and may be constantly on the line engaged in the direction of its details; each person is personally known to him, and all questions in relation to its business are at once presented and acted upon; and any system however imperfect may under such circumstances prove comparatively successful.

In the government of a five hundred miles in length a very different state exists. Any system which might be applicable to the business and extent of a short road would be found entirely inadequate to the wants of a long one. and I am fully convinced that in the want of system perfect in its details, properly adapted and vigilantly enforced, lies the true secret of their [the large roads’] failure; and that this disparity of cost per mile in operating long and short roads, is not produced by a difference in length, but is in proportion to the perfection of the system adopted.[18]

New methods had to be invented for mobilizing, controlling, and apportioning capital, for operating a widely dispersed system, and for supervising thousands of specialized workmen spread over hundreds of miles. The railroads solved all these problems and became the model for all large businesses. The main innovators were three engineers, Benjamin H. Latrobe of the Baltimore and Ohio, McCallum of the Erie, and John Edgar Thomson of the Pennsylvania. They devised the functional departments and first defined the lines of authority, responsibility, and communication with the concomitant separation of line and staff duties which have remained the principles of the modern American corporation.

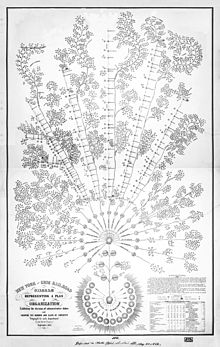

Illustrative organization chart, 1855

As general superintendent McCallum in 1855 designed an illustrative organization chart of the New York and Erie Railway, which is considered to be the first modern organization chart,[19] which was compiled and draw by the civil engineer George Holt Henshaw. On the chart is written,[20] that the diagram represents a plan of organization, and exhibits the division of administrative duties and shows the number and class of employees engaged in each department, and is dated September 1855.

The chart explains that the diagram is compiled from the latest monthly report and indicates about the average number of employees of each class engaged in the Operating Department of the railroad company. It shows the powers and duties of each individual and to whom they are subject to report.[20] It further describes:

- By inspection it will be seen that the Board of Directors as the fountain of power, concentrates their authority in the President as the executive Officer, who in that capacity directly controls those officers who are shown on the Diagram at the termini of the lines diverging from him, and these in their turn, though all the various ramifications down to the lowest employee control those who terminate the lines from them.

All orders from the Superior officers are communicated in the above order, from superior to subordinate to the point of desired; thereby securing despatch in their execution and maintaining proper discipline without weakening the authority of the immediate superior of the subordinate controlled by the order thus transmitted. Each individual therefore holds himself responsible only to his immediate superior…”[20]

Furthermore, a table is added showing the number of offices and employees classed. First were listed the employees in the five divisions of the New York & Erie Railroad divided in workers at the station, on trains, on repairs of trucks, and on repairs of bridges and buildings.[20]

The chart was thought lost for years, and only located at the Library of Congress after many years of research after Alfred Chandler had suggested its existence. It was found by Charles D. Wrege (1924-2014)[21] and Guidon Sorbo Jr. (1927-2008) in 2005.[22] They suggested that the visualization of the organizational tree probably was inspired by the shape of a local flower Salix caprea (goat willow, also known as the pussy willow, or great sallow).[23]

Principles of management, 1856

As General Superintendent of the New York and Erie Railroad, McCallum developed new ideas about a modern system of management. In his 1856 report he formulated the following requirements:[24]

Table shows the rate and direction of subordination for a first class railroad, from Vose (1857).

- A system of operations to be efficient and successful should be such as to give to the principal and responsible head of the running department a complete daily history of details in all their minutiae. Without such supervision the procurement of a satisfactory annual statement must be regarded as extremely problematical. The fact that dividends are made without such control does not disprove the position, as in many cases the extraordinarily remunerative nature of an enterprise may insure satisfactory returns under the most loose and inefficient management.

McCallum presented the following general principles for the formation of such an efficient system of operations,[25] reprinted in Vose (1857)[26]

-

- First. A proper division of responsibilities.

- Second. Sufficient power conferred to enable the same to be fully carried out, that such responsibilities may be real in their character.

- Third. The means of knowing whether such responsibilities are faithfully executed.

- Fourth. Great promptness in the report of all derelictions of duty, that evils may at once be corrected.

- Fifth. Such information to be obtained through a system of daily reports and checks that will not embarrass principal officers nor lessen their influence with their subordinates.

- Sixth. The adoption of a system, as a whole, which will not only enable the general superintendent to detect errors immediately, but will also point out the delinquent.

About the core principle of management, he summarized:[27]

- All that is required to render tho efforts of railroad companies in every respect equal to that of individuals, is a rigid system of personal accountability through every grade of service.

Vose (1857, p. 416) added, that all subordinates should be accountable to, and directed by, their immediate superiors only. Each officer must have authority, with the approval of the general superintendent, to appoint all persons for whose acts he is held responsible, and to dismiss any subordinate when in his judgment the interests of the company demand it.[26]

American Civil War, 1862-65

In the American Civil War 11 February 1862, McCallum got appointed Military Director and Superintendent of the Union railroads, with the staff rank of colonel, by Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War. McCallum had authority to “enter upon, take possession of, hold and use all railroads, engines, cars, locomotives, and equipment that may be required for the transport of troops, arms, ammunition, and military supplies of the United States, and to do and perform all acts… that may be necessary and proper… for the safe and speedy transport aforesaid,” he wrote in his 1866 report.[28] McCallum’s view was that his organization “was a great construction and transportation machine, for carrying out the objects of the commanding generals.” As superintendent of the New York and Erie Railroad McCallum had developed a reputation as an autocratic leader, running his railroad with “strict precision and stern discipline.” But to his credit, he combined his engineering and administrative talents with his pleasant personality to make a success of his tenure.[28]

McCallum and Capt. Hurlbert on Lookout Mountain.

As McCallum’s assistant was appointed Herman Haupt, who also was called to service in early 1862. The two worked practically independent from each other.[29] While McCallum was the administrative head of the U.S. Military Railroads, Herman Haupt was in charge of the operations of the railroad in the field. At the time that McCallum assumed his duties, the seven-mile road from Washington to Alexandria, Virginia, was the only railroad in federal government control. By May 1862 the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, which ran from Alexandria southwest toward Orange, Virginia, was an important supply line, as was the Manassas Gap Railroad, which covered the territory between Manassas Junction and Front Royal and Strasburg.[28] By the end of the war, the U.S. Military Railroads had, at different times during the war, used parts of 17 railroads as military lines in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania and 23 in Tennessee, Georgia, Mississippi, Arkansas, and North Carolina. In addition, the small Construction Corps grew from about 300 men in 1863 to nearly 10,000 men by the end of the war.[28]

During his stint as superintendent of the U.S. Military Railroads, McCallum fulfilled the function of liaison officer between the government and the many railroads on the one hand, and manufacturers of railroad equipment on the other. His greatest success was supporting the western operations from Nashville and Chattanooga under Gen. William T. Sherman in summer of 1864,[28] by successfully supplying General Sherman‘s army of 100,000 men and 60,000 animals.”[4] “The successful supply of Sherman’s army in its campaign from Chattanooga to Atlanta was the most outstanding achievement of the military railroads,” later reported Thomas Weber in The Northern Railroads in the Civil War, 1861–1865.[28]

In 1865 McCallum participated in the organization of the Funeral and burial of Abraham Lincoln. Following his death by assassination, the body of Abraham Lincoln was brought from Washington, D.C. to its final resting place in Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois, by funeral train, accompanied by dignitaries. The Department of War designated the route and declared railroads over which the remains passed as military roads under the control of McCallum as director and superintendent of United States Military Railroads. No person was allowed to be transported on the cars except those authorized by the War Department, and the train never moved at speeds of more than 20 miles (32 km) an hour to avoid any accidents.

To McCallum was due much of the efficiency of the railroad service during the civil war. He was brevetted brigadier-general of volunteers “for faithful and meritorious services,” 24 Sept. 1864, and Major General, 13 March 1865. On 31 July 1866, he was mustered out of the service. In the same year he published a report on the military railroads during the war, written with James Barnet Fry.

American timber bridges

The 1863 article entitled “American Timber Bridges” by the Institution of Civil Engineers described that:

- Timber-bridge building has become an especial branch of Engineering in the United States, and there are several firms who devote their whole time to this subject. The large number of bridges required for 30,000 miles of railway has necessarily given great field for experience, and many designs having been tried, the plan of bridge now the most general, becomes of course the more valuable. Of the firms alluded to, one of the most eminent is that of Mr. D. C. McCallum, an Engineer of high standing, who was for several years the manager of the New York and Erie Railway, a length of 460 miles, exclusive of branches. The Inflexible Arched Truss being now probably in more general use than any other bridge… The first mention [in Great Britain] of this bridge, and of Mr. McCallum’s admirable system of working trains by the electric telegraph, will be found in Captain Galton’s Report on the Railways of the United States.[30]

The National Cyclopedia of American Biography (1897) confirmed, that the inflexible arched truss introduced by McCallum has probably been in more general use in the United States than any other system of timber bridges.[31] A 2012 Historic American Engineering Record confirms that:

- According to Raymond Wilson’s article “Twenty Different Ways to Build a Covered Bridge,” Technology Review May 1971, an estimated 150 McCallum truss bridges once existed. In 1858, there were 55 McCallum truss spans on the New York & Erie Railroad and an advertisement for “McCallum’s Inflexible Arch Truss” in Poor‘s 1860 “History of the Railroad and Canals of the United States”, lists 20 railroad lines using this type of truss.[32][33]

This success didn’t last much longer. McCallum continued to construct bridges during the Civil War, but the type of bridge fell out of favor. It was obsolete by 1870, because it was difficult to frame[32] and metal constructions had taken over.[34]

Nowadays the only remaining example in the world of the McCallum truss is the Percy Covered Bridge (1861),[35] ironically an automobile and footbridge. It crosses the Chateauguay River at Powerscourt, Québec, between the municipalities of Elgin and Hinchinbrooke.

Management principles

Chandler (1977) stipulated that:

- McCallum’s principles and procedures of management, like his organization chart, were new in American business. No earlier American businessman had ever had the need to develop ways to use internally generated data as instruments of management. None had shown a comparable concern for the theory and principles of organization. The writings of James Montgomery [a British textile manager with American experience] and the orders of plantation owners to their overseers talked about the control and discipline of workers, not the control, discipline, and evaluation of other managers. Nor does Sidney Pollard in his “Genesis of Modern Management” note any discussion about the nature of major principles of organization occurring in Great Britain before the 1830s, the data at which he stops his analysis.[36]

McCallum’s work drew national and international attention. Chandler (1977) recalled that

- Poor had McCallum’s organization chart lithographed and offered copies for sale at $I a piece. Douglas Galton, one of Britain’s leading railroad experts, described McCallum’s work in a parliamentary report printed in 1857. So too did the New York State Railroad Commissioners in their annual reports. Even the Atlantic Monthly carried an article in 1858 praising McCallum’s ideas on railroad management.[37]

McCallum’s ideas were further developed by others, such as Chandler (1956) explained: “expert railroad engineers as George Vose and John B. Jervis wrote much on the principles of systematic management which McCallum had first articulated and Poor had expanded upon.”[38]

16 Th8 2019

20 Th8 2019

21 Th8 2019

20 Th8 2019

21 Th8 2019

20 Th8 2019